Journey to My Father’s Holocaust

by longformphilly

David Lee Preston | Inquirer Sunday Magazine | April 1985

“Tell your children of it, and let your children tell their children, and their children another generation.”

Joel 1:3

LAST YEAR, I PERSUADED MY FATHER to journey with me to the places of his past. He did not say much about these places while I was growing up, but our bookshelves brought me closer to some of them. They had names like Auschwitz and Buchenwald, and in the books, I saw photographs of living skeletons in prison garb with tattooed numerals on their arms, of mutilated children, of twisted bodies piled as high as mountains or strewn in vast pits, of solitary souls fastened dead against electrified barbed-wire fences. These were not like the places other fathers had come from.

If I wanted to catch a glimpse of my father in his youth, I could peer into the sound box of his mandolin and find the tiny photo portrait he had glued inside as a boy. This was his first mandolin, the one his uncle had given him in Rovno, my father’s birthplace in the Ukraine.

Our bookshelves also held an old photo album my father had compiled. Like the mandolin, it had survived the Holocaust hidden in France, and if my father had not outlived the Nazi death camps, no one would have come to retrieve it; the frayed photos of family members would have been lost to eternity.

My father was the only one in his family who survived – a French-educated engineer, a Jew whose technical training kept him alive at Auschwitz. Now, quick-witted and vigorous as ever, he was nonetheless alone and depressed after my mother’s death in 1982. The numbered arm that held me as a child was still strong, but his hair was graying. If we were to undertake such a trip, this was the time.

We traveled to the Soviet Union (which now rules the region in which my father was born and raised); to France (where he had been arrested by the Gestapo); to Poland (where he had endured two years in Auschwitz and other camps until the Soviet army approached), and to East Germany (where he had been imprisoned in Buchenwald until its liberation 40 years ago this month). During the trip, my father was both guide and interpreter, facile with the languages everywhere we went. But the trip was grueling; it taxed my father’s body and soul.

Why, then, would I ask my father to return to these places for the first time since the Holocaust? Why subject him to the painful memories after all these years? And why open the life of a private man to the scrutiny of readers?

Because the child of the survivor has a special obligation: If I am David Lee, my father’s son, it is because somehow I am also David Laeb, my father’s father. If I was born from the survivor’s seed, then somehow I also rose from the victim’s ashes.

And so I have made the journey through time and place, back to the world of my father and of his father, to a world that somehow also must be mine. I have made the journey because one day I shall transmit the seed anew, and I must know and feel. I have done so because the future holds no meaning or purpose without the past, and because the story of an entire people can be told in the retracing of my father’s steps and in the retelling of his life.

If I am a son, I must begin to understand my father. If I am a Jew, I must begin to understand my people. If I am a human being, I must begin to understand my legacy.

This was my duty.

I ALREADY KNEW GEORGE PRESTON THE suburban American, whose painting of my mother hung in their bedroom, and whose humorous blueprint for a “baby boy arrangement” announced my “specifications” as well as my birth. I knew the devoted family man, the father who didn’t spare the rod but spoiled his two children anyway, who gave the neighborhood bully a good licking after I’d been picked on. I knew the chess player who allowed me to retract my lousy moves and sometimes let me win. I knew the man who married a Jewish educator despite his own ambivalence toward organized religion, who stood in the background for 30 years while his wife, also a survivor, became Delaware’s pre-eminent public speaker on the Holocaust – and who himself began accepting invitations to speak after she died.

I knew George Preston, the faithful and industrious Du Pont Co. engineer whom they called at home from Chattanooga or Waynesboro or Seaford when the spinning machines broke down, and they needed quick advice. I knew this supremely disciplined man, this early riser, this tree planter, auto mechanic, refrigerator fixer, porch builder.

But when he sometimes would take out the old, battered, round-back mandolin that still contained a boy inside, the mournful melodies he strummed bespoke a man who had known other times in distant places, far from Wilmington, Del. – far from me.

It was this man – Grisha Priszkulnik, Georges Priszkulnik, Auschwitz No. 160581, Buchenwald No. 124049 – whom I really needed to know.

ROVNO, WHERE HE WAS BORN, WAS a bustling commercial center in the Ukraine, part of Poland at the time. Also spelled Rowne, it was a city whose 22,000 Jews constituted about 70 percent of the population. Jews had lived in the city since the 1500s, and by 1900 it was a wellspring of Jewish culture.

David Laeb Priszkulnik (pronounced prish-KUHL-nik) already had a thriving lumber business in Rovno when he and his wife, Sonia, had their first child. They named him Gersh, in memory of her grandfather, and they called him Grisha.

As soon as Grisha was old enough, he began helping out at work. Grisha even helped his father build the family a new home on the gravel road beside the railroad tracks; the duplex was the first house in Rovno with hot and cold running water.

Grisha’s artwork adorned the walls: watercolor paintings of street scenes, charcoal portraits, abstract designs, an oil painting of his grandmother. Grisha and his mother would spend many happy hours together in the dining room – Sonia embroidering at one end of the long table and Grisha at the other end hunched over the mandolin on his lap, his ear against the table, strumming melodies for his mother. Grisha also serenaded his younger brother, Yasha, a shy lad whom he loved dearly. And he and his cousin Aaron – his closest friend – enjoyed playing their mandolins together.

The Priszkulniks belonged to the smaller of the two synagogues in Rovno and traditionally sat in the first row of seats. Grisha learned Hebrew from a private tutor hired by his father.

Sometimes, the family would go for picnics to the outskirts of town, to the area called Sosenki – the Little Pines – where every year on the agricultural holiday of Lag B’Omer, the Jewish children of Rovno would celebrate with song and dance.

Jewish life was unhindered by the Polish government. But if a Jewish child ventured outside town, he risked being assaulted by Ukrainians, Poles or Russians. Grisha suffered many a beating.

When Grisha was 17, his mother became gravely ill with an undiagnosed ailment. David Laeb summoned a professor from Lvov to examine her, but her condition deteriorated. Sonia died on a Friday night, while Grisha and his father sat helplessly at her bedside. No one could come for her body on Saturday, the Sabbath day, so she remained in the house until Sunday. They buried her in the Jewish cemetery, and her photograph was inset in an enamel oval at the top of the tall tombstone.

It was his first confrontation with death, but in time, Grisha recovered, his creative zest undiminished. He hoped for a career as an artist. But David Laeb tried to steer his son toward a profession in which he could better support himself.

So Grisha went to Vilna and Warsaw to study engineering, then to France in 1935 to complete his education. Two years later, he graduated from the University of Caen with a master’s degree in electrical and mechanical engineering.

Meanwhile, the Nazis were seizing more and more power. Jews already had lost their jobs in Germany. Grisha applied for a visa to enter the United States. He was denied.

Returning to Rovno in August 1938, Grisha pleaded with his father to leave Poland. But David Laeb was not ready. Like almost everyone else he knew, he did not take Hitler seriously. “Why not stay with us?” he implored his son. ”You’ll have a business here. “

David Laeb had never ventured beyond the borders of Eastern Europe, but his son already knew a safer life in France and intended to go back there to find work. In April 1939, David Laeb drove Grisha by horse and buggy along the gravel road from the house to the railroad station.

Tears streamed down their cheeks as they stood together on the train platform – the proud father and his adult son. And even as Grisha boarded the train for Warsaw, neither man uttered the sad, inexorable truth: They would never see each other again.

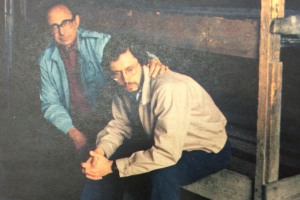

FORTY-FIVE YEARS LATER, ON THE SAME RAILROAD tracks on which he had departed, my father returned to Rovno with his son, David Lee. Holding a photograph of my father’s house, it was I who recognized it from the window of the train.

After we had settled in at the modern Soviet hotel called Mir (“Peace”), my father’s curiosity got the better of him: Almost immediately, we headed for his house.

As we walked from the hotel, it was clear that Rovno had changed: We passed tall apartment buildings; a large, new opera house; a cinema; statues and posters of Lenin. We passed my father’s synagogue, now painted the same somber yellow as other public buildings in the city. Revealing no trace of its own past, the synagogue holds the city’s archives.

Finally, we reached the gravel road along the railroad tracks and approached the house. Chickens walked in the road and in trash along the railroad bed. The house was painted an earthy brown, with rickety wooden stairs. It hardly looked like the fancy home it once was.

Curious neighbors gathered around us. Two girls stood on the front stoop, giggling. They ran inside.

Then the front door opened: A peasant woman in bare feet emerged. She wore a violet garment, her hair wrapped in a shawl. She was friendly. Yes, she said, she lived there, but only for a few years.

The house had been subdivided. Three families now lived where the Priszkulniks once did. The woman took us to the rear of the house; a man came out and invited us in.

My father and I entered a kitchen that once was a bathroom. We sat in the living room; it once had been the Priszkulniks’ kitchen. It was sparsely furnished, somewhat unkempt. The man said he had lived there only a few years, the third or fourth occupant since the war.

Where is the Priszkulniks’ furniture? Where is my father’s artwork?

We didn’t bother to ask: These poor folks wouldn’t know. They didn’t know the Priszkulniks. They knew only that the Jews who once lived in the area were gone.

ON NOV. 5, 1941, THE NAZIS ANNOUNCED that all Jews in Rovno without work certificates were to gather in the main square the following day with all their belongings. The next morning, 18,000 Jews showed up. Even those with work certificates came; they did not want to be separated from their loved ones.

The Nazis chose this day for a reason: The Communist world was celebrating the anniversary of the Russian Revolution – one of many things for which the Nazis blamed the Jews.

Now, in the snow, German soldiers, helped by Ukrainians, Poles and others, herded the Jews of Rovno away from the square, telling them they were being taken to a work detail. Grisha was in France when David Laeb and his fellow Jews were taken out beyond the city. The process lasted an entire day.

Along the way, they were told to drop all their belongings. Then they were led farther, to the Sosenki, the place of so many happy Lag B’Omer celebrations. There, the Jews were confronted with three enormous ditches.

David Laeb and the others were surrounded by armed policemen with dogs. They were ordered to undress. They were lined up at each ditch – the men, the women and the children.

The police offered to spare Rabbi Maiofes, whom they saw in the crowd. But the rabbi refused. “Where my flock goes,” he said, “so goes their shepherd. “

And so the Nazis and their helpers machine-gunned David Laeb Priszkulnik and 18,000 other Jews.

ONE MUST KNOW WHERE TO LOOK FOR THE Jews of Rovno. No markers have been erected in their memory. About two miles outside the city, set off from the paved highway, Sosenki can be reached only by a dirt road so steep and rough that our taxi driver would not attempt it. A Jew who had survived the Holocaust by joining the Russian army directed us to the spot. We arrived in the rain.

So this was where they ended up, the Jews of Rovno: an area roughly 120 yards by 25 yards, unkempt, rugged, muddy, overgrown with weeds, surrounded by a rusted fence since the end of the war. In one corner, a broken shovel.

Was this perhaps a shovel that had been used to dig the massive pits? Or was it used by the Latvian man who had participated in the Rovno killings, who returned a few years ago with his son, in search of gold teeth? Working at night, they dug up the remains. Some elderly Jews who visited the spot found the disarray and notified Soviet authorities. Police staked out the area and arrested the two men while they were digging. But no effort was made to repair the disturbed ground.

We walked inside the fence, trampling over the innocent thousands, the entire families who were murdered because they were Jews. And as we walked slowly in the mud, we found human bones, jaws, teeth. This was the epitaph for the Jews of Rovno.

Hesitantly, my father and I withdrew, moving back outside the rusted fence. Together, we faced the mass grave, and, in tenuous voices, we recited the Kaddish, the ancient Jewish prayer for the dead. Then we turned and walked slowly on the gravel road, down the hill in the rain.

THE FOLLOWING DAY, WE WENT TO FIND my grandmother’s grave. Because she had died before the Holocaust, my father knew exactly where to look for it; we walked there easily from the hotel.

Alas, the grave was gone. The Russians, who themselves had suffered terribly at the hands of the Nazis, had bulldozed the Jewish cemetery of Rovno. In its place: a playground.

My father had prepared himself for what we had seen at Sosenki because he had been informed of his family’s fate after he had survived his own harrowing Holocaust. But he was not prepared for this: His mother, our lone relative in all of Europe whose grave was marked, now was left to obscurity, too, as if she never existed. My father was disgusted. “Why couldn’t they just leave the Jewish cemetery alone?” he asked. “Why did it bother them? Wasn’t it enough that the Jews were gone? “

Just beyond the playground, in the newly turned earth where bulldozers were landscaping the hillside, we found more Jewish bones. And in a wooded area on the hillside lay strewn both whole and fragmentary Jewish gravestones. I did not have to scratch too deeply into the ground to uncover still more of them – even a Star of David buried in the Soviet soil.

Again, my father and I recited the Kaddish. Again, we turned and walked down a hillside, heading for the city’s memorial to its victims of fascism – an impressive bronze monument with a sign bearing a red flame. The inscription, written boldly in Ukrainian, seemed like the final affront: ”Nothing is forgotten,” it says. “No one is forgotten. “

WHEN THE GERMANS INVADED France in 1940, Georges Priszkulnik was working for an engineering firm in Lille, near the Belgian border. The company was about to relocate to the south of France, but Georges did not want to risk waiting. In the heat of the summer, he took a bicycle and headed for the beach, hoping to board a boat carrying British troops across the English Channel and out of northern France.

The road was full of people, horses, wagons. German bombs rained down on them. Georges hid in ditches, covering his body with his bicycle. When he arrived at Dunkerque, he was barred from boarding the ships to England, which were overcrowded with British troops. It was mid-June. German soldiers soon arrived and blocked the exits to the south. Georges had no alternative but to return to Lille. The city was occupied by Germans. Georges’ company had moved south. On June 21, within days of his return, France surrendered.

After a brief stint as an interpreter for the French production crew at the Lille theater controlled by the Germans, Georges took a job in 1941 with a French engineering consulting firm. As the Nazi clampdown on Jews began in earnest, Georges ignored the announcements that Jews were to register and to wear yellow patches bearing the word Juif inside a Star of David.

On Aug. 8, 1942, as he emerged from a Lille market, Georges was arrested by the Gestapo and charged with “anti-German activities. ” He was taken to Gestapo headquarters, where he was beaten unconscious, then to a Gestapo prison guarded by French police.

Finally, he was put on a passenger train to Malines, a Belgian town north of Brussels, where he and Belgian Jews were loaded onto cattle cars and deported to Nazi-occupied Poland.

In slave labor camps, wearing the Star of David now, Georges and the other prisoners built railroads over a period of months. They also were tortured by having to carry gravel and sand at a running pace from one location to another, then to carry it back again. It was in these camps that Georges first heard that Jews were being exterminated at a place called Auschwitz.

One day, while working on the railroad, Georges watched a sealed train pass by – boxcars packed with people on their way to Auschwitz. He saw people looking out from the cars through tiny openings. And from that train came the loud cry of a youth calling to Georges and the other workmen on the track: ”Yidn, nemt rache!” – “Jews, take revenge! “

One of the prisoners approached the train; a guard shot him. Later, another prisoner, a Jewish doctor from Paris, removed the bullet, saving the man’s life.

Before long, Georges and his fellow workmen were loaded onto freight cars, too – told that they were headed for work in German factories. For days, 50 locked cattle cars, each crammed with 100 people, rolled toward an unknown destination.

On the night of Nov. 3, 1943, the train came to a stop, the seals on the cars were broken, and the doors slid slowly open. With sticks, the SS men and kapos (criminals given supervisory functions by the SS) drove Georges and the others from the boxcars in the cold night. “Raus, und schnell!” they ordered. “Out, and fast! “

Georges jumped to the ground. This was Auschwitz-Birkenau, a barbed-wire- enclosed barracks town spread over 8,000 acres in southern Poland. The main gate at Auschwitz proclaimed: “Arbeit Macht Frei” – “Work Brings Freedom.”

A young officer barked orders, dividing the new inmates into two groups. Those sent in one direction went directly to the gas chambers. The others, including Georges, were considered fit to work. The officer was chief physician of the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp, the man who greeted the arrival of every transport. His name was Josef Mengele.

Georges was terrified. His possessions were taken away, and he shivered in the rags he had been given to wear. He was brought to a barracks, where his hair was clipped off. A number was tattooed onto his left forearm. No longer was he Georges Priszkulnik. Now he was 160581.

THE SLOGAN IS STILL ON THE GATE, BUT THE CAMP is a museum now. We stayed in the Auschwitz Museum Hotel, a former SS building.

Two and a half million Jews were murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau. In all, four million innocent men, women and children died there – most of them in gas chambers set up to eradicate Jews, gypsies, homosexuals, political prisoners and others.

Auschwitz was the name the Germans gave the camp they established in 1940 near the Polish town of Oswiecim, 37 miles west of Krakow. It was the camp that was known to the world, the “model” camp the Red Cross visited, the camp where brick buildings still stand largely intact. The museum calls it Auschwitz I.

But it was at Birkenau – or Auschwitz II – a camp set up in 1941 near the Polish town of Brzezinka, and hidden from the Red Cross and other visiting groups, that the mass killing was accomplished.

The Auschwitz buildings now contain rooms of glass-enclosed exhibits with mountains of the victims’ eyeglasses, shoes, clothing, shaving brushes, false appendages, suitcases, hair. One building is devoted to the martyrdom of the Jews. Inside, a tape-recorded cantor wails a continuous “El Malei Rachamim” (“God, Full of Compassion”), a Jewish hymn for the dead. In a guest book, visitors from around the world scribble impressions and messages. Many speak of the inadequacy of the museum, the distortion of truth, the fact that only this single building hints at the historical purpose of the camp: to annihilate the Jews. A popular message on these pages is the Hebrew inscription “Am Yisrael Chai,” “The people of Israel live. ” In bold letters, here and there, the book reveals the phrase “Never Again. “

In a large room filled with file cabinets, the museum maintains documents that show the precision with which the Nazis recorded their deeds. In one drawer, containing information about blood tests and other records of the ”SS Hygienic Institute,” we found six index cards pertaining to “Georg Priszkulnik, No. 160,581. “

At Birkenau, only one wooden barracks remains; the others – including my father’s Block 11 – are gone, torn down after the war. The vestiges of the five gas chambers and adjoining ovens still can be visited in the woods behind the camp. My father hardly recognized the place: When he was an inmate, it was filled with people, dead and alive, and the sounds of suffering.

As we passed beneath the main watchtower on our way back to our hotel, we met five local boys, all in their early teens. My father asked whether they knew what had happened here, and they seemed eager to show what they knew.

“This was where many Poles were killed,” offered one boy.

“Jews, too?” we asked.

“Yes,” said one. “Also Jews. But mostly Poles. “

“Why did they kill Jews?” my father asked.

“Because Hitler was part Jewish,” a boy answered. “And he was jealous

because Jews were smarter than he. “

I urged my father to show the boys his tattoo, to see their reaction. He rolled up his sleeve. They gasped. One of them backed away. Slowly, the reality hit them: This man had been a prisoner here.

After we had exchanged addresses with a couple of the boys, we parted ways. My father and I agreed that they seemed friendly, mature, intelligent. We wondered how much they knew of what went on inside those barbed-wire fences, beneath that watchtower, only four decades earlier.

AT BIRKENAU, 160581 SAW SS MEN PULL children away from their mothers and throw them into trucks headed for the gas chambers. He saw an SS man thrust his walking stick down a dying man’s throat. He saw SS men set their dogs on inmates. He saw prisoners who could not take it anymore jump onto the electrified barbed wire.

He wore a small red triangular patch bearing the letter “F,” for French. Living in the wooden barracks of the quarantine section, where new inmates were temporarily housed, he still had a tiny loose-leaf booklet containing a few engineering notations and precious photos of his family. Among the few items he had brought to Birkenau, it was the only one he had managed to hold on to: a last link with his past.

One day, it was announced that technically trained people were needed. Thousands of prisoners came forward, hoping for a chance to go far away from the continuously smoking chimneys of the crematoria. Engineers from the Siemens Co. tested the prospective workers. 160581 passed an oral test. Next, he had to drill a hole in a metal plate and to file a square opening to a precision of one-one-hundreth of a millimeter through which a cube could fit.

Six workers were chosen. One was 160581. He would be housed in Block 11 at Birkenau, along with 25 other engineers. Their assignment: to transform an abandoned four-story brick building several miles away at Bobrek into a modern, one-story plant. To do this job, they were given ropes to climb up, and hammers to knock bricks down. In the bitter cold, 160581 and the others wore thin prisoner uniforms and wooden shoes.

Every evening, they were brought back to Block 11 until the plant and its barracks were completed. Block 11 was laid out like the other barracks: three tiers of wooden bunks on both sides, with an oven running down the middle for heat. 160581 slept with five other prisoners on a board, sharing a single blanket. He slept in the same clothes he wore during the day. Several times, men lying beside him died.

At Block 11, the Siemens workers were to receive better treatment than the other prisoners so they could be strong to build the plant. But the “senior inmate” in charge of Block 11 was a particularly vicious Silesian who delighted in abusing the Siemens workers. His name was Emil Bednarek, and he maintained a strict regime: If he found a speck of dust on a prisoner’s blanket, he would beat him with his walking stick. Bednarek hit 160581 over the back so often that he was almost paralyzed.

Bednarek forced his prisoners to do painful exercises, which he called ”sport. ” During one running exercise, a prisoner was unable to continue, and fell exhausted onto the ground. 160581 saw Bednarek kick his shiny boots into the man’s chest until he was dead. On another occasion, while an SS man watched, Bednarek placed his walking stick against a fallen prisoner’s throat and stood on it. Then he rocked back and forth until the prisoner was dead. The SS man offered hearty congratulations. After Bednarek killed people, he returned to his room to pray.

160581 was so hungry that at one point he sneaked away from Block 11 in the middle of the day, when he was supposed to be working, and headed for the kitchen to beg for some soup. An SS officer stopped him.

“What the hell do you have there?” the man barked.

It was the little booklet with the photos of his family. The SS man grabbed the book.

“These are pictures of my parents,” 160581 said.

The officer laughed uproariously. “You stupid bastard,” he said. “You think you’ll ever see your parents again? You see those chimneys? ” He pointed to the crematoria. “That’s where you’ll end up. “

The officer beat and kicked him. Then he walked away with the book. 160581 was left writhing on the ground.

In May 1944, after the Siemens workers had readied the Bobrek plant, they began to be housed nearby. At the plant, 160581 and his co-workers were put to work making dies to be used in fabricating electrical components for German submarines.

It was only a matter of time before 160581 became ill with typhus from the constant exposure to lice. As part of the Siemens group, he was not sent to the gas chambers despite his illness. Instead, he went to the camp ”hospital” adjacent to one of the crematoria. There he lay for several weeks without medical treatment. His fever was high, and most of the time he didn’t know what was going on around him.

Among the prisoners in the hospital, 160581 recognized a face: It was the Jewish doctor from Paris, the man who had extracted the bullet from the prisoner at the work camp. He was working in the hospital as a nurse. One day, the doctor told 160581 that no matter how sick he still was, he should get discharged from the hospital and report back to work. A new transport of inmates was expected, the doctor said, and all the sick prisoners would be sent to the gas chambers.

Summoning his last ounce of strength, 160581 willed himself to leave the hospital and return to his job.

THE SUN IS SETTING OVER BIRKENAU on the first day of June, and I am standing in the middle of the railway tracks, alone, inside the camp. To my left is the building where Mengele stayed, and beyond that the women’s camp. I stand where the selections were made. Ahead of me, the gas chambers and the ovens. At my right, the men’s camp. Behind me, along a sidewalk outside the camp, a boy in shorts is pushing a baby in a carriage. Two men in a cart are pulled by a horse. Another boy, maybe 5 years old, rides past on a tiny bicycle.

It is quiet but for the sounds of the country evening: a cow’s moo, the music of many kinds of birds, a dog’s bark, frogs’ croaks from the pit where a little more than 40 years ago, human beings were drowned. In the distance, a train. Wooden watchtowers on either side. At my back, the main gate.

I turn right and enter the men’s camp through the opening in the barbed- wire fence. Before me, two endless rows of naked concrete posts bent at the top, the rusted barbed wire stripped away.

The brush is thick, the wildflowers many and diverse. A brick chimney is all that remains of Block 11; the same is true of the other barracks. I kneel to inspect a daisy, studying it for a few minutes, marveling at its intricate beauty. Then I rise again to face the rows of chimneys and cement fence posts, stretching far into the distance on every side.

I try to imagine it as it was, the constant movement of human bodies assuring that not a blade of grass could grow, let alone a daisy. All around me in the tall grass are weeds, mushrooms, rocks, pieces of rusted metal. Somewhere toward the sunset, the call of a cuckoo pierces the air. The sun is red now, sinking farther into the woods where they burned my people.

I would like to say that I can imagine what it was like for my father in this place for 14 months – each day a new battle to remain alive, each minute an eternity of pain and fear. But I can’t; my mind is incapable of imagining such things. I cannot see my father here, clinging desperately to life, nor can I see the others who suffered and died.

As I walk back along the railway tracks toward the main gate, I stop and turn around for one last time. Standing erect, I look toward the gas chambers and crematoria at the far end. More people were murdered here than at any other single spot in history. What gives me the right to stand here now?

With the watchtower at my back, I begin to retrace my steps, moving ever closer to the gas chambers, with an irrational thought of keeping vigil nearby. I would be unafraid of the coming darkness, unfazed by the cold of the night.

But how long could I sit, before the rains would come? Eventually I would grow hungry, and what purpose would it serve? If I sing a lullaby to the one and a half million infants and children murdered during the Holocaust, would they be comforted? I could not return a single one of them to life. If I shed a tear, would it matter?

I spin round again, walking slowly along the tracks, leaving the millions of my murdered people to spend another lonely night unattended but for the crazy, mindless cuckoo bird marking time in the distance.

The sun has set on Birkenau.

ON THE NIGHT OF JAN. 17, 1945, with the Russian army approaching, the Nazis evacuated the camps. More than 14 months after he had become a number, 160581 set out with the other Siemens workers, joining thousands of prisoners from Auschwitz, Birkenau and other camps, marching northwest. Ten thousand prisoners were led on foot about 50 miles through the cold of winter. Some tried to hide in the snow. For many, it was a death march.

When the prisoners arrived in Gliwice, SS men loaded them onto flatcars. After the train was rolling, some prisoners jumped off and tried to flee. A few made it, but most were shot. 160581 did not jump; he didn’t trust the local populace to save him.

As the cars rolled slowly across the countryside, snow fell, and 160581 caught the fresh, crisp flakes in a tin container; no food ever tasted so wonderful to him. The train passed through Czechoslovakia, losing more passengers with every mile. At Prague, 160581 found himself with a loaf of bread and a container of water, among hundreds thrown into the train by kind- hearted Czechs at the risk of their lives.

More days passed, and the train came to a stop outside Weimar. 160581 looked around him. He knew that he was still alive, but he didn’t know how much longer he could last. All around him, for days on end, fellow travelers had fallen by the wayside. And now, when the SS men pulled him off the flatcar, he found himself once more in a camp with barbed-wire fences, railway tracks and watchtowers. This time, the slogan on the gate said: “Jedem das seine” – “To each, his due. ” This was Buchenwald.

THE MASSIVE MEMORIAL BELL tower, the impressive sculpture of resistance fighters, the three huge circular pits within which are buried the remains of the victims of Buchenwald – my father and I visited them all. We saw the well-preserved ovens where the dead were burned; the lampshades made from human skin; the shrunken heads; the pictorial tattoos saved from dead prisoners for the collection of the camp commandant’s wife.

But the Buchenwald museum’s only reference to the Jews is a line on the wall: “Jewish prisoners paid a high price in blood. They were special victims of the revenge, sadism and murder practiced by the SS.” As at Auschwitz, the emphasis is on documenting the socialist struggle against the barbaric fascist oppressors. The Buchenwald brochure explains that the museum “spans the period from the establishment of the fascist dictatorship by German imperialism to the self-liberation of the Buchenwald camp – a glorious chapter in the anti-fascist resistance struggle of the German people who were led in this battle by the Communist Party. “

And the brochure adds: “Many more Jews than people of other nationalities were killed by the fascist barbarians. “

IN BUCHENWALD, HE WAS issued a cloth patch bearing a new number. Although the number “160581” remained on his arm, he was now 124049.

He was assigned to help move wooden wagons filled with heavy stones from the steinbruch, the quarry. The pace was fast, and whoever fell from the strain was beaten to death by snarling SS men. On other days, while Weimar was being bombarded by Allied planes, 124049 was among the inmates whose job it was to dig through the rubble of the city for German bodies.

Although the planes passing overhead gave some hope to the inmates, large groups now were being evacuated from the camp to prevent them from falling into the hands of Allied troops. A short distance from the camp, they were machine-gunned.

124049 was determined to remain in the camp. He noticed that several inmates wore white armbands bearing numbers. These inmates were assigned to clean the barracks and to remain in the camp until the final transport. 124049 went to his barracks, tore off a piece of his shirt, and with a needle and thread, sewed a black trim around the edge. He wet the graphite of a pencil and printed some numbers on the cloth. Within minutes, he had made an armband identical to those worn by the privileged inmates.

Haggard and beyond hunger, 124049 now had survived for three long years – sometimes because of luck, sometimes because of his own wits – while those around him had perished. Now, in the waning weeks of the war, he summoned his last ounce of will to remain alive.

On April 11, 1945, before the SS could kill the last prisoners, American tanks plowed through the barbed wire and liberated Buchenwald. 124049 thought it was a mirage. SS men, caught by surprise, threw off their military uniforms and dressed themselves in prison garb. Ecstatic prisoners took over the camp, picked up guns and climbed onto American tanks. Georges Priszkulnik, a walking skeleton at 80 pounds, found a gun and helped hold the SS men in a barracks for the American troops.

MY FATHER WAS NOT THE ONLY Jew from Rovno who survived. Many fled to Russia to escape the Nazis, some joining the Russian army. They became citizens of the Soviet Union.

One was my father’s cousin, his boyhood chum, Aaron. They had corresponded since the war but had not seen each other since my father boarded the train out of Rovno in 1939. Now aging and frail, a stroke victim, Aaron lives in Kuibyshev, a city on the Volga that is closed to foreigners. Aaron obtained permission from Soviet authorities to meet us in Moscow with his daughter, Rosa.

In the parking lot of a hotel on the outskirts of Moscow, my father and his cousin were reunited after 45 years. What was there in that hug, what thoughts, what images went flying through the minds of these cousins, these two sons of Rovno, what chemistry in their tears at that instant?

From the parking lot, we all traveled to the Moscow apartment of another Rovno Jew. There, we spent an evening singing along with records of Hebrew and Yiddish songs; eating potato latkes and other traditional Jewish food lovingly prepared by the man’s wife. These Jews were very much alive. Aaron and I sat across a table from each other. We had never met before. Several times, he told his cousin that he only wished he could speak directly to me. But language prevented it. And so we sat, staring, smiling. It was a conversation in a universal language: the language of a common bond, the language of understanding.

We all raised our cups of wine, and I recited Shehecheyanu, the ancient Hebrew prayer of thanksgiving, ever so slowly to be sure these Soviet Jews – who rarely have an opportunity to hear such things – could savor every word:

“Blessed art thou, O Lord our God, who has sustained us and enabled us to reach this festive occasion. “

Everyone said, “Amen. “

And then, our cups still full and raised, we affirmed, “L’chaim” – “To life. “

AFTER WE RETURNED FROM OUR journey, I took out the old, timeworn photo album my father had compiled before the Holocaust. I saw him playing chess, table tennis, strumming his mandolin. I saw him in Paris, in Warsaw, in Brussels – a debonair cosmopolitan. I saw my father walking down a Rovno street with his cousin Aaron, both men nattily attired. I saw his younger brother, Yasha, the quiet one, smiling while he skated on the ice with a hockey stick: Murdered before he could reach adulthood, he remains the innocent, skating, smiling Jewish boy. He was my uncle.

But of all the photographs from my father’s past, the one that commanded my unwavering attention was a tiny sepia print in which my grandfather, David Laeb, is reading a newspaper. I could see him more clearly now, after our trip, and I took pity on him. Like so many of the Jews of Eastern Europe, he was blinded by naivete, relying on the past and accepting of the future, reading the news without facing reality.

And yet, when David Laeb stood on the train platform on that day in 1939 and said goodbye to his first-born offspring, he was casting out his only real hope for survival – a son who was well-educated, worldly wise, prepared to face whatever might confront him.

If David Laeb survives through his son, who came through hell intact, then surely he also survives through his grandson, who was born free and never experienced adversity or the pain of hate.

Just as I carry my grandfather’s name, my younger sister carries the Hebrew names of our two grandmothers. As children of Holocaust survivors, it is both our privilege and our obligation to go forward in a manner worthy of those for whom we are named.

WHETHER THEY DIED BY MACHINE GUN, like the Jews of Rovno, or in the gas chambers of Birkenau, whether they lie piled behind rusted fences like that at Sosenki or near elaborate, wreath-bedecked monuments like those at Auschwitz and Buchenwald, the Jews of Eastern Europe are gone.

For the survivor’s child, the omnipresence of death overcomes the imparted stories of life, the sadness inevitably destroys the joy, and the landscape of the journey becomes a vast, macabre museum of fear and despair. The people working in the fields, the peasants on the dirt road beside the tracks in Rovno, the men eating Wiener schnitzel in a Weimar restaurant – all are tainted with some measure of guilt. If they did not take the Jews to slaughter, they watched them go.

In 1965, my father flew to Frankfurt, West Germany, to testify against Emil Bednarek in the first Auschwitz war-crimes trial. Bednarek’s lawyers actually had invited him as a defense witness, believing that as a specialist, he had received less severe treatment than other inmates.

Facing Emil Bednarek and 20 other defendants, my father told how he had seen Bednarek kick an inmate to death, how he had forced inmates to take cold showers and then to stand outside until they froze to death. After a 21-month trial, Bednarek was convicted of murder in at least 14 cases, and received a life sentence.

But what about the other Emil Bednareks? What about Mengele, who reportedly is still at large? And what about the thousands of other Germans, Ukrainians, Poles, who walk the streets of Europe, South America, the United States and elsewhere – unaccused because the plaintiffs are dead, unprosecuted because the victims cannot testify?

How many German homes still use the mattresses filled with Jewish hair from Auschwitz? How many homes across Eastern Europe are furnished with the plundered possessions of the Jews? And how many people still wear the Jews’ clothing, or hoard the gold that the SS melted down from the teeth of their gassed victims?

What about the Soviets, who tear down cemeteries, who erect no monuments, who demonstrate the will to forget?

And what of the local boys we met at Birkenau – the grandchildren who inherit a world without Jews and who must be the hope for the future? What will they know of the past?

“Blessed be Jesus Christ,” one of the boys wrote to my father. “Did you and your son return home in good health? “

For the survivor, Eastern Europe is no museum but a place from a previous life, with faces and languages from the past. He carries his own guilt, knowing that those who died also deserved to live. The survivor did not need this trip, as his child did. The survivor has no use for Eastern Europe anymore.

On Hanukah, I gave my father a mandolin that was made in Montana. It is flat-backed and extremely thin, unlike traditional European models, but it has a rich, full tone, and he enjoys playing it. His boyhood mandolin hangs on the wall now, an old and trusty friend, retired, while the old melodies ring true on the new model.

Although the instruments may change, memory can touch the strings so that the melodies live on. Maybe I am David Priszkulnik, or David Preston. Give me a name or a number, it doesn’t matter. What counts, in any of us, is what is transmitted in heart and soul from one generation to the next. What survives is the ability to remember even the unimaginable, the will to learn the unspeakable, the capacity still to love.

For there remains the opportunity to stand alone beneath the setting sun at Birkenau and know that tomorrow it will rise again – to allow the realization of the enormity of the crime, of the cruelty, the pain and the suffering, to come crashing down upon one’s head and yet to summon strength from the ashes, to realize that daisies still grow there.

For all God’s children, there remains the opportunity to choose love over hatred, knowledge over ignorance, understanding over apathy, compassion over ambivalence – the chance to learn the sad melodies of the past so that we might create from them a hopeful song for the future.

I promise you, George Preston: This lesson I shall never forget.

Writer bio: David Lee Preston is an assistant city editor at the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Philadelphia Daily News and Philly.com. Preston, who wrote for the Inquirer for 17 years, is a native of Wilmington, Delaware. This is the second article in a trilogy that documented his parents’ experiences during the Holocaust. This piece was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing in 1986.

Part I: A Bird in the Wind

Part III: A Story for my Mother

David~ what an amazing piece of writing. Thank you for sharing this.

I wish I could have gone on this journey with my parents

My father died too young, and we didn’t talk about his experience as much as we do now. My beloved mother died a few months ago. They both survived the Holocaust, Auschwitz, Buchenwald,etc. They created three

generations!

I’m glad you had this journey with your dad

Annie Nottes

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Annie.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for the sensitive and inspiring words you shared. Your touched my heart with the story of your Journey with your father. My father, who was able to escape to Cuba in 1939, was never ready to return for his Journey. He never was able to look me in the eye and tell me the story. Although what your father went through was absolutely horrific, there is a sense of bonding between you and your father after the trip. I will cherish this story for the remainder of my life and thank you for your eloquent words and feelings.

LikeLike

Thank you, Steve.

LikeLike

My Father was from Rovno too his name was Misha Goldberg and he ran away from the Germans to USSR IN 1941 with his sister Roza and his parents Anna and Benajamin ,two of brothers were students in France.

The names are Joseph Goldberg who lived in Lille and his brother Jacob who was caught by the French and deported through Drancy to Auschwitz and was murdered there .

So there is a great possibility that they knew each other .

My name is Benjamin Godder

LikeLiked by 1 person

My father was also born in Rovno. His name was Yitzhak Kobylanski (Robert Koby), his brother was Moshe and his parents were Ansel and Raizal. They were hidden by different families and all survived.

LikeLike

Sobering, powerful, inspirational.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLike

I have heard many accounts about holocaust survivors but this account has touched me the most, what an amazing journey for father and son.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Phyliss.

LikeLike

Extremely powerful, interesting, & heartwrenching

LikeLike

Thank you.

LikeLike

Both of my parents are of Jewish heritage. My mom had her own nightmare of a story that she did share with us. Her grandparents lived in Austria and had 2 large houses. My mom wanted to go back to one of the houses in Baden Baden and was refused entry. She sat outside and cried. After my great grandparents were taken away from Austria and sent to Poland, they were killed along with a great aunt. My mom’s name was changed along with her siblings and mom spent many years in Catholic boarding schools in England and then served in the British Army where she met my Philadelphia dad. I was born right at the end of the war. Mom had to adjust to a new culture and new beginnings all with nightmares of the past war. Mom never got over the war and died at 94. Mom talked about her grandparents houses, the help, the grand artwork and the sad memories. Mom introduced us to Jewish foods and temples but didn’t practice her religion as she was brought up not to. My children do know of their heritage which is so important. They know about what happened to their Jewish family and now we are educating their grandchild. I have enjoyed your narrative and feel that it is very important to know our parents stories as it is part of us. Part of the people we never got to meet. Part of our life story now. Thank you for sharing your heritage.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for reaching out, Judith. Sorry it took me so long to respond, but I just saw your note. I wish you and yours good health and a fulfilling journey through your heritage. Please accompany me on mine by joining my mailing list on my website to receive my free monthly newsletter. Best wishes, David

LikeLike

[…] Part II: Journey to My Father’s Holocaust […]

LikeLike

[…] Part II: Journey to My Father’s Holocaust […]

LikeLike

I’m so glad I took the time to read of your journey back with your beloved father.

My own father was a survivor from Czechoslovakia/Hungary Carpathian Mountains area. His family were taken to Auschwitz in 1944 and killed on arrival. We always thought of returning to his hometown , but an uncle did and nothing much was left of recognition. The grave and stone where my grandfather is buried , he died before the war, still stands.

Thank you for sharing your journey back.

LikeLike

I read your fathers story and I am reminded of my fathers Auschwitz experience.

I too am the daughter of 2 survivors.

I am amazed at how much you knew

I know a lot less but I research as much as I can

I have to give myself some time to rest after your article so I can read the other stories

Please let me know if you speak anywhere

Thanks for your fabulous writing.

Debby Kanner.

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Debby. All good wishes to you on your journey. Please join my mailing list. Best regards, David

LikeLike

Thank you very much, Daniel. Sorry it took me so long to respond, but I just saw your note. Good luck on your journey. Please accompany me on mine by joining my mailing list on my website to receive my free monthly newsletter. Best wishes, David

LikeLike

Dear David

I read your beautifully written article with great interest

I,too am a child if 2 survivors

My father also survived Auschwitz and was liberated from Buchenwald

I will take time to digest your article and then read your other ones

My father never really spoke much about his life. He was very scarred. Physically and emotionally

Childhood was difficult

LikeLike